by Samantha Couture, MHS Nora Saltonstall Conservator & Preservation Librarian

Welcome to Part 3 of our series on conservation at the MHS. Here, we will discuss a few of the conservation treatments that Samantha performs in our lab. The purpose of any conservation work is to reverse or repair damage to extend the useability and lifespan of the item or provide access for research or exhibition. The benefits of doing a treatment or repair are weighed against any potential risks to the item, the time involved, and the research value of the piece.

There are many variables that affect treatment and its effectiveness, such as the type of paper, kinds of inks and other media, the nature and extent of the damage, and any ‘inherent vice’ present in the paper or ink. Effective treatments can reduce dirt and pollutants that degrade paper and media, remove acids that cause embrittlement, remove tape and adhesives that stain and damage paper, flatten a document so that it can be framed or stored, and repair tears and fill lost areas to strengthen and stabilize the paper. There are some things treatments can’t do, like reverse brittleness of paper or leather, darken faded inks, or remove some types of discoloration.

One collection at MHS that needed a significant amount of attention is the Perry-Clarke family papers. When our processing archivists began to arrange and describe the family correspondence, they discovered significant amounts of soot and fire damage to the documents. Soot is acidic and sticky, and clings well to paper. Over time, it can cause the underlying paper to become stained and brittle. It’s also very easy to get soot from one document to another while handling. Additionally, some of the items were torn or in pieces, and unable to be handled by researchers.

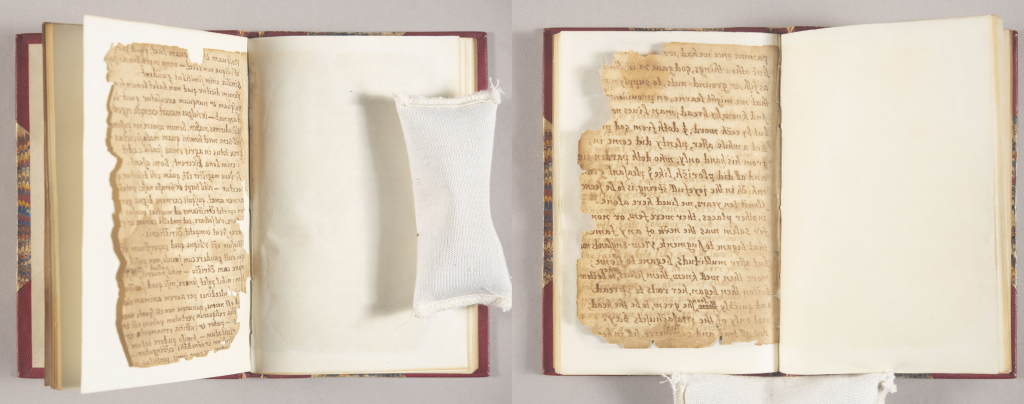

Luckily, the paper of most of the fire damaged items was of good quality and was strong enough to mend. This letter, written by James J. Clarke on January 28, 1840, to Alfred, was badly damaged and in pieces. To allow the item to be handled, the sections, weakened areas, and tears were mended using Japanese paper pre-coated with adhesive. The pre-coated tissue was cut into the shapes of the tears and losses. Then the adhesive is reactivated with alcohol and attached to the area to be mended.

Right: After treatment

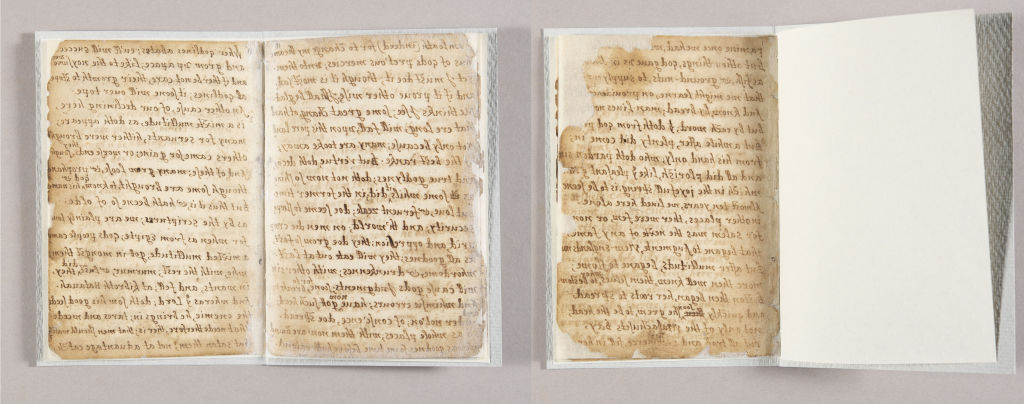

The MHS has several manuscripts by Mayflower passenger William Bradford. We looked at one of these in Part 2 when we examined Bradford’s “Dialogue.” The binding was beautifully made at the MHS in the nineteenth century, but it was difficult to see all the text, since the pages didn’t open fully. In 2023, one leaf of the pamphlet needed to go out on exhibit. We decided to remove the entire manuscript from the binding and after exhibition, mend and sew it into a paper cover, which is most likely what Bradford would have done originally.

Right: Bradford’s Dialogue after treatment

Another of our Bradford manuscripts, ‘Some observations of God’s merciful dealing with us in this wilderness, and His gracious protection over us these many years’ [fragment], had also been bound in the 19th century. The pages were attached along the spine to blank leaves making some of the text impossible to see. The manuscript was stained and too fragile to be used.

Because of the staining and acidity of the paper, Samantha decided to wash the manuscript. Washing refers to many types of water and solvent solutions used in paper conservation. Washing removes soluble acids, dirt, and can lighten stains. Removing acids makes the paper more flexible and less likely to break or tear. An added treatment done during the washing process neutralizes the iron in iron gall ink to prevent further corrosion. After washing, the pages were reinforced and lost areas filled with Japanese paper. After treatment the pages were digitized and then they were resewn into a paper cover.

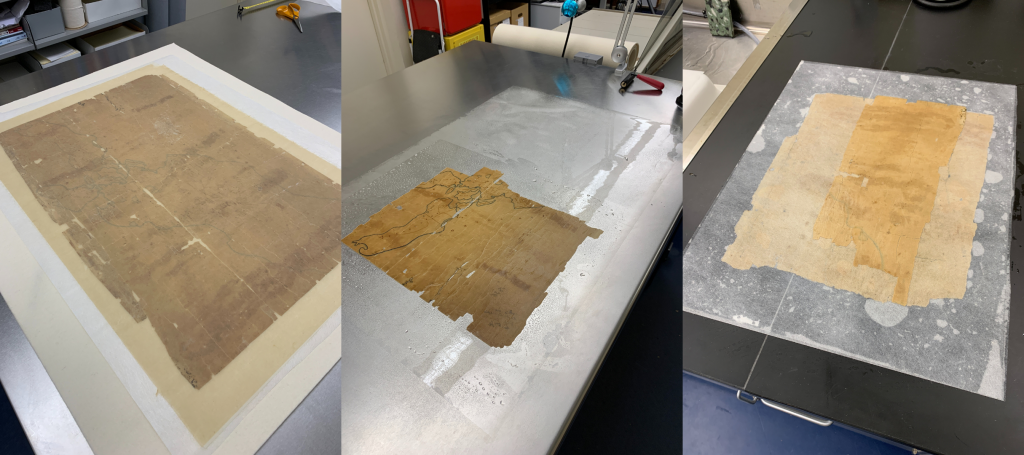

The MHS has a significant map collection. Like many, this hand drawn map of Naushon and the Elizabeth Islands made in 1836 was attached to a cloth backing, nailed to wooden dowels, and then rolled for many years. The new acquisition arrived with cracks, tears, water stains and was so tightly rolled it was impossible to keep flat.

First, the cloth and adhesive were removed from the back of the map. Then the pieces of the map were washed. To align the pieces of the map, it was first placed wet between mylar and eased into place. The mylar allows the map to then be turned upside down and lined with Japanese paper. The map was then dried between wool felt and weight. Now, the map is stored with the rest of the collection and is ready to be used by researchers.

Below is the finished treatment after drying and flattening.

There are many activities besides direct treatments that we do at the MHS that contribute to the preservation of our collections. In our next post, we will discuss the building environment, storage and handling practices, budgeting and time management, documentation, and disaster preparedness.